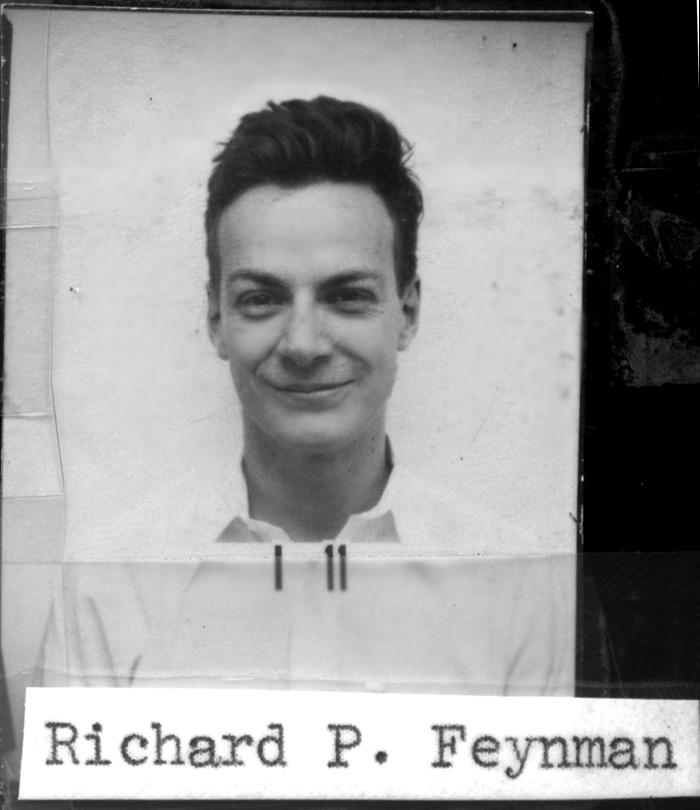

From Los Alamos From Below by Richard Feynman

I was working in my office one day, when Bob Wilson came in. I was working—[laughter] what the hell, I’ve got lots funnier yet; what are you laughing at?—Bob Wilson came in and said that he had been funded to do a job that was a secret and he wasn’t supposed to tell anybody, but he was going to tell me because he knew that as soon as I knew what he was going to do, I’d see that I had to go along with it.

So he told me about the problem of separating different isotopes of uranium. He had to ultimately make a bomb, a process for separating the isotopes of uranium, which was different from the one which was ultimately used, and he wanted to try to develop it. He told me about it and he said there’s a meeting…I said I didn’t want to do it. He said all right, there’s a meeting at three o’clock, I’ll see you there. I said it’s all right you told me the secret because I’m not going to tell anybody, but I’m not going to do it. So I went back to work on my thesis, for about three minutes. Then I began to pace the floor and think about this thing.

The Germans had Hitler and the possibility of developing an atomic bomb was obvious, and the possibility that they would develop it before we did was very much of a fright. So I decided to go to the meeting at three o’clock. By four o’clock I already had a desk in a room and was trying to calculate whether this particular method was limited by the total amount of current that you can get in an ion beam, and so on.

I won’t go into the details. But I had a desk, and I had paper, and I’m working hard as I could and as fast as I can. The fellows who were building the apparatus planned to do the experiment right there. And it was like those moving pictures where you see a piece of equipment go bruuuup, bruuuup, bruuuup. Every time I’d look up the thing was getting bigger.

And what was happening, of course, was that all the boys had decided to work on this and to stop their research in science. All the science stopped during the war except the little bit that was done in Los Alamos. It was not much science; it was a lot of engineering. And they were robbing their equipment from their research, and all the equipment from different research was being put together to make the new apparatus to do the experiment, to try to separate the isotopes of uranium.

I stopped my work also for the same reason. It is true that I did take a six-week vacation after a while from that job and finished writing my thesis. So I did get my degree just before I got to Los Alamos, so I wasn’t quite as far down as I led you to believe.

One of the first experiences that was very interesting to me in this project at Princeton was to meet great men. I had never met very many great men before. But there was an evaluation committee that had to decide which way we were going and to try to help us along, and to help us ultimately decide which way we were going to separate the uranium. This evaluation committee had men like [Richard] Tolman and [Henry DeWolf] Smyth and [Harold] Urey, [Isidor I.]Rabi and [J. Robert] Oppenheimer and so forth on it. And there was [Arthur] Compton, for example.

One of the things I saw was a terrible shock. I would sit there because I understood the theory of the process of what we were doing, and so they’d ask me questions and then we’d discuss it. Then one man would make a point and then Compton, for example, would explain a different point of view, and he would be perfectly right, and it was the right idea, and he said it should be this way. Another guy would say well, maybe, there’s this possibility we have to consider against it. There’s another possibility we have to consider. I’m jumping! He should, Compton, he should say it again, he should say it again! So everyone is disagreeing, it went all the way around the table. So finally at the end Tolman, who’s the chairman, says, well, having heard all these arguments, I guess it’s true that Compton’s argument is the best of all and now we have to go ahead.

And it was such a shock to me to see that a committee of men could present a whole lot of ideas, each one thinking of a new facet, and remembering what the other fellow said, having paid attention, and so that at the end the decision is made as to which idea is the best, summing it all together, without having to say it three times, you see? So that was a shock, and these were very great men indeed.

This project was ultimately decided not to be the way that they were going to separate uranium. We were told then that we were going to stop and that there would be starting in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the project that would actually make the bomb and that we would all go out there to make it. There would be experiments that we would have to do, and theoretical work to do. I was in the theoretical work; all the rest of the fellows were in experimental work.

The question then was what to do, because we had this hiatus of time since we’d just be told to turn off and Los Alamos wasn’t ready yet. Bob Wilson tried to make use of his time by sending me to Chicago to find out all that I could about the bomb and the problems so that we could start to build in our laboratories equipment, counters of various kinds, and so on that would be useful when we got to Los Alamos.

So no time was wasted. I was sent to Chicago with the instructions to go to each group, tell them I was going to work with them, have them tell me about a problem to the extent that I knew enough detail so that I could actually sit down and start to work on the problem, and as soon as I got that far go to another guy and ask for a problem, and that way I would understand the details of everything. It was a very good idea, although my conscience bothered me a little bit. But it turned out accidentally (I was very lucky) that as one of the guys explained a problem I said why don’t you do it that way and in a half an hour he had it solved, and they’d been working on it for three months. So, I did something!

When I came back from Chicago I described the situation—how much energy was released, what the bomb was going to be like and so forth to these fellows. I remember a friend of mine who worked with me, Paul Olum, a mathematician, came up to me afterwards and said, “When they make a moving picture about this, they’ll have the guy coming back from Chicago telling the Princeton men all about the bomb, and he’ll be dressed in a suit and carry a briefcase and so on—and you’re in dirty shirtsleeves and just telling us all about it.” But it’s a very serious thing anyway and so he appreciated the difference between the real world and that in the movies.