Published: Wednesday, July 20, 2016

Updated: November 14, 2018

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, many Americans were suspicious of first-generation Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans and accused them of espionage. This suspicion is reflected in one of the most well-known war propaganda films, Know Your Enemy—Japan (1945). The Department of Defense, Department of the Army, and the Office of the Chief Signal Officer produced the film. Frank Capra, famous for It’s a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, directed it.

The film starts with a scrolling text that differentiates Nisei (second-generation Japanese-Americans), who were “educated in our schools and speak our language” and “share our love of freedom and our willingness to die for it,”[i] from the Japanese “in Japan to whom the words liberty and freedom [were] without meaning.”[ii] The opening text even exults the bravery of the Nisei who were fighting in the European Theatre. However, these nuances are lost by the end of the film. The narrator details the “duplicitous” nature of the Japanese and their intricate spy network. He talks about how the “officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy, masquerading as fishermen, piloted tiny boats equipped with diesel engines and radio sending cells” and “fish[ed] for tuna off the coast of California.”[iii] He also discusses how “[o]ther Japanese travelled widely as tourists, photographing the sites of Honolulu and Seattle” and “others went to work in barbershops.”[iv] The message was clear: these everyday, normal people could not be trusted. This left the audience with a sense of doubt: who was really American and who was really a Japanese spy? Without mentioning it, Know Your Enemy seemed to implicitly justify the relocation and internment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans throughout the war.

Even though this film was released 3 years after Executive Order 9066, it illustrates the fear and suspicion of people with Japanese ancestry that led to President Roosevelt’s order to “evacuate” Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) and Japanese-Americans to relocation centers two months after Pearl Harbor. The process stripped them of their homes and many of their possessions. Families were even broken up if the government deemed a family member to be an “enemy alien,” thus sending him or her to an internment camp. It took four decades and multiple petitions before the U.S. government formally apologized in 1988.

Executive Order 9066

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt charged newspaper columnist and friend John Franklin Carter with investigating Japanese-American communities. Carter sent Chicago businessman Curtis Munson to the West Coast to meet with intelligence officers, FBI agents, and Japanese-Americans. In November 1941, Munson sent Carter a report that concluded that “[t]here will be no wholehearted response from the Japanese in the United States” to support the Japanese war effort and emphasized instead the loyalty of Japanese-Americans to America. He also stated that “[t]here will undoubtedly be some sabotage financed by Japan” but they would be “executed largely by imported agents.” Carter then forwarded the Munson Report to the President with a one-page memorandum that stated that “[f]or the most part the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.”[v]

The attack on Pearl Harbor “unleashed a storm of anti-Japanese hysteria” that was directed towards Issei and Nisei. [vi] Lt. Gen. J.L. Dewitt expressed this anti-Japanese racism in his infamous quote: “A Jap is a Jap.” [vii]

Despite the findings of the Munson Report, the President’s Cabinet discussed a policy of removing the Issei and Nisei populations. Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Secretary of Navy Frank Knox favored this removal policy out of military necessity, while Attorney General Francis Biddle argued against it, citing individuals’ constitutional rights.[viii]

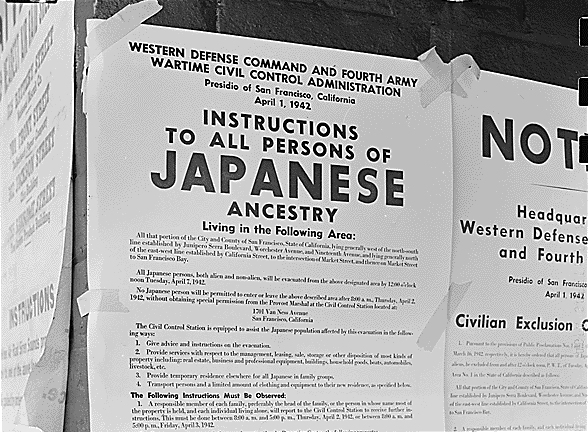

President Roosevelt ultimately sided with Secretaries Stimson and Knox and issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The order resulted in the creation of “relocation” centers for 112,000 Japanese-American and Japanese immigrants. [ix]

Entitled “Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas,” the Order began with the words, “Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage.” [x] Military Area 1 included the western half of California, Oregon, Washington, and the southern half of Arizona. [xi]

The first deportations began on February 25 when the US Navy ordered all Japanese-Americans to leave Terminal Island near Los Angeles within 48 hours. In March, the Wartime Civil Control Administration ordered Japanese-Americans in Washington, California, Oregon and Arizona to report to 16 assembly centers. [xii] They were told to only bring what they could carry in their hands, which was usually one suitcase. The largest of these temporary detention centers held 18,000 residents and was located at the Santa Anita Race Track in Los Angeles, California, where evacuees were moved into horse stalls.[xiii] There was not enough housing in the assembly centers, so the government built military-style barracks in nearby parking lot complexes to house everyone.

At these assembly centers, Japanese-Americans were processed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which had been established for this express purpose. In May 1942, the WRA completed building ten relocation centers in California, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas and began transfer of Japanese-Americans from the assembly centers.[xiv]

Even though the U.S. government termed the camps “relocation camps” or “relocation centers,” the newly built camps had military barracks, barbed wire, and guard towers and searchlights. As historians Everett Rogers and Nancy Barlit observe: “This terminology implied that the Japanese-Americans were simply being relocated from the West Coast to other parts of the country. This euphemistic label, however, would not call for barbed wire, armed guards, and searchlights. The guns pointed inside.”[xv]

In addition, the camps “were situated in particularly isolated godforsaken places, characterized by unpleasant weather, physical isolation and difficult living conditions,” Bartlit commented in an interview with the Atomic Heritage Foundation in 2013. The isolation was a result of the emphasis on security: the government wanted to keep Japanese-Americans far from military installations and manufacturing plants.

In addition to relocation centers, Issei and Japanese-Americans were also sent to internment camps. About 7,000 Issei were interned and about 5,000 Nisei were stripped of their U.S. citizenship and declared to be “aliens.” The Smith Act of 1918 gave the U.S. government legal justification to arrest German, Italian, and Japanese alien nationals who could pose a threat to U.S. national security. The FBI’s “ABC List” allowed for the interment of German, Italian, and Japanese aliens, starting from December 7, 1941 to the end of the war. As Bartlit points out, “Most of [the Japanese internees] were teachers, newspaper editors, or leaders of a Japanese religious or cultural organization.” Unlike relocation centers, internment camps fell under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice. [xvi]

The United States viewed interned Issei and Nisei as prisoners of war. At four main internment camps, these individuals awaited hearings. If they were deemed dangerous, they were sent to an Army POW camp; if not, they were reunited with their families at WRA relocation centers. Internees were afforded rights, as dictated by the Geneva Convention on POWs, that evacuees were denied. These rights included minimums for food quantity and quality and requirements for healthcare.[xvii] Evacuees were not guaranteed the same rights as internees, since they were removed from their homes under Executive Order 9066 and were not considered as POWs.

The differences between relocation centers and internment camps were stark. In the relocation centers, evacuees adhered to strict rules and curfews. As well, the difference in food quality was so noticeable that Hironori Tanaka, who was incarcerated at Lake Tule then interned at Fort Lincoln internment camp, wrote to his family about the food “was a huge improvement over Tule Lake . . . The food was excellent.” [xviii]

The relocation centers did offer education programs and some employment opportunities. Evacuees also organized to create Japanese language classes and other programming to maintain their culture. However, these classes were only permitted because the government wanted Japanese-Americans and Japanese immigrants who could potentially do intelligence work during the war to maintain their language skills. Famously, in Tule Lake Camp, a strong self-identification with Japanese culture led to a creation of a pro-Japan group that later rioted and had its leaders sent to the Santa Fe Internment Camp. [xix] Ironically, this contradicted the spirit of keeping Japanese-Americans away from military installments.

“Why they were brought as ‘dangerous enemy aliens’ away from the coast as potential spies and brought to the CCC Camp [in Santa Fe], to the gateway to the biggest secret of all of World War II is kind of a puzzle,” said Bartlit. “It was in the city limits. It was not very far from where Dorothy McKibbin had her office at 109 E. Palace Avenue.”

The WRA also commissioned photographers to document life at camps. In 1942, WRA photographer Dorothea Lange took photos at the Manzanar relocation center of the barracks being constructed and the uncertain early days of Japanese incarceration. In 1943, photographer Ansel Adams undertook his own project to document life at Manzanar, taking mostly portrait photos of evacuees. A third photographer of Manzanar was evacuee and photographer Toyo Miyatake. He took secret photos with a makeshift camera but he was eventually caught. However, the camp director allowed him to take photographs openly.[xx]

After the War

Following the end of the war, the Japanese-Americans were released and many returned home to find their goods stolen and properties sold.[xxi]

In the 1970s, Asian-American political figures such as Senators Daniel K. Inouye and Spark Matsunaga of Hawaii and Congressmen Norman Y. Mineta of San Jose and Robert T. Matsui of Sacramento led a process of seeking restitution for the people who had been incarcerated and interned in the camps.[xxii] Senator Inouye had served in the all-Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team and was awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest US military honor, for his service.[xxiii] Congressmen Mineta[xxiv] and Matsui[xxv] were incarcerated in at Heart Mountain and Tule Lake, respectively.

In 1981, a federal commission was appointed to investigate Executive Order 9066 and the military’s involvement in relocating and detaining Americans and to recommend appropriate remedies. Their findings were published in 1982 in a report entitled Personal Justice Denied. The report stated that “[b]road historical causes which shaped decisions were race, prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan.”[xxvi]

More importantly, the Commission wrote that “not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage, or 5th column activity was committed by an American citizen of Japanese ancestry or by a resident Japanese alien on the West Coast.”[xxvii]

Seven years later, Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act. The surviving 82,219 Japanese-Americans who had been incarcerated were each sent a formal apology letter from the President and awarded $20,000 each.[xxviii] The first payments were made in October 1990 to the oldest Japanese-Americans, and payments were paid out until 1999.[xxix]

There have been memorialization and preservation efforts. On June 29, 2001, a memorial to Japanese-American Patriotism in World War II was constructed in Washington, D.C. after efforts from Congressman Mineta and Congressmen Matsui. The memorial depicts two cranes with barbed wires tying their wings.[xxx]

Additionally, Manzanar, Minidoka, and Tule Lake are National Historic Sites. Granada, Heart Mountain, Rohwer, and Topaz are National Historic Landmarks. Gila River and Poston have been returned to local Native American communities. Jerome is now mostly private farmland. Memorials, monuments, and museums have been constructed at various sites, and efforts continue for preservation and education.[xxxi] Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, a National Historic Site in Bainbridge, Washington, commemorates one of the first groups of Japanese-Americans to be evacuated. They were sent to either Manzanar or Minidoka relocation camp in Idaho.

Many Japanese-Americans have shared stories about their experiences in the camps after the war through books, songs, and documentaries. In 2012, actor George Takei, who was incarcerated at Tule Lake, wrote and starred in Allegiance, a Broadway musical about life at the incarceration camps.

Critical Responses

Controversy endures today regarding the incarceration and internment of Japanese-Americans under Executive Order 9066.

“$20,000 did not even cover what they had lost in terms of careers. Their property was often lost, stolen, not protected,” said Bartlit. “$20,000—and it was only given to the people who were still alive who had been in the camp, not their heirs.”

Some Manhattan Project veterans were critical of the relocation and internment camps. “We have a blot on our history in this country as a democracy that we will never outlive,” commented Jacob Beser, the only person to be aboard both strike planes that bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“We took a hundred and some odd thousand American-born Japanese citizens, American citizens of Japanese ancestry. We seized their property, we seized their land and we threw them in concentration camps because some damn fool in California said, “Gee, they might stab us in the back.””

Question of Terminology: Evacuation, Incarceration, or Internment?

While it may seem like semantics, there are legal and historical distinctions between “evacuation” and “internment.” Furthermore, defining these terms adds another layer of nuance and complexity to the treatment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans and their experiences during World War II.

“Evacuation” and “relocation” were the preferred terms of the time used when referring to the removal of all people with Japanese ancestry, including Americans, as ordered by Executive Order 9066. The United States did not consider evacuees as “enemy aliens,” nor did the FBI and naval intelligence deem them potentially dangerous. As such, they were never charged with crimes or received trials. The WRA was in charge of evacuees.[xxxii] Relocation centers included Tule Lake, Manzanar, Poston, Gila River, Topaz, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, Granada, Jerome, and Rohwer.[xxxiii]

“Internment” refers to the “legal scheme under which a warring country may incarcerate enemy soldiers and selected civilian subjects of an enemy power.”[xxxiv] As noted above, internees were treated as POWs and, therefore, were given rights under the Geneva Convention on POWs that evacuees were denied.[xxxv] The Department of Justice was in charge of internees.[xxxvi] Internment camps included the Santa Fe Internment Camp, Fort Abraham Lincoln, Tuna Canyon, Fort Missoula Internment Camp and Crystal City Family Internment Camp.[xxxvii]

The WRA at the time tried to make similar distinctions. In a memorandum sent to Tule Lake, D.S. Myer, Director of the WRA, wrote:

“The evacuees are not ‘internees.’ They have not been ‘interned.’

Internees are people who have individually been suspected of being

dangerous to the internal security of the United States, who have been given

a hearing on charges to that effect, and have then been ordered confined in

an internment camp administered by the Army.” [xxxviii]

This article tries to reflect historical uses and legal distinctions when using the terms “evacuation,” “relocation,” “internment,” “evacuees,” and “internees.” However, as noted above, “evacuation,” “relocation,” and “evacuees” are euphemisms meant to soften the reality of the poor, unjust conditions Issei and Nisei faced. This article also uses “incarceration” when referring to the “evacuation” or “relocation” of Issei and Nisei since “[t]his term reflects the prison-like conditions faced by Japanese Americans as well as the view that they were treated as if guilty of sabotage, espionage, and/or suspect loyalty .” [xxxix]

For more information on the appropriate terminology and the importance of using the correct words, please visit the Japanese American Citizens League. There is a comprehensive guide called Power of Words Handbook that further elaborates on this subject.

Special Thanks to James Tanaka for submitting corrections.

CITATION

“A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II.” National Park Service. Updated in April 1, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/articles/historyinternment.htm.

“Ansel Adams Gallery.” National Park Services. Updated December 11, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/photosmultimedia/ansel-adams-gallery.htm.

Associated Press. “Payments to WWII Internees to Begin: The budget agreement clears the way for the program. The oldest survivors will be the first to receive the $20,000 checks.” The LA Times. Published October 1, 1990. http://articles.latimes.com/1990-10-01/news/mn-1299_1_budget-agreement.

“Daniel K. Inouye, A Feature Biography.” United States Senate. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Featured_Bio_Inouye.htm. Accessed September 28, 2018.

“Dorothea Lange Gallery.” National Park Services. Updated July 29, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/photosmultimedia/dorothea-lange-gallery.htm.

Himel, Yoshinori H.T. “Americans’ Misuse of ‘Internment.’” Seattle Journal for Social Justice. Vol. 14. No. 12. 2016. 797-837.

Know Your Enemy—Japan. Directed by Frank Capra. 1945; Washington, DC: The U.S. National Archives, 2016. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvcE9D3mn0Q.

“Interning Japanese Americans.” National Park Services. Updated November 17, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/worldwarii/internment.htm.

“Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism during World War II.” National Park Service. Updated February 16, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/places/japanese-american-memorial-to-patriotism-during-world-war-ii.htm.

“Japanese Relocation During World War II.” The National Archives. Updated April 10, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation.

“John Franklin Carter.” Densho Encyclopedia. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/John%20Franklin%20Carter/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

“Locating the Site–Map 2: War Relocation Centers in the United States.” National Park Services. https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/89manzanar/89locate2.htm. Accessed September 28, 2018.

“MATSUI, Robert T.” History, Art & Archives–United States House of Representatives. http://history.house.gov/People/Detail/17631. Accessed September 28, 2018.

MOLOTSKY, IRVIN, and SPECIAL TO THE NEW YORK TIMES. “Senate Votes to Compensate Japanese-American Internees.” The New York Times. Published April 21, 1988.

https://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/21/us/senate-votes-to-compensate-japanese-american-internees.html.

Munson, Curtis. “The Munson Report.” Published in November 1941. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/japanese_internment/munson_report.cfm.

Nash, Nathan C. “WASHINGTON TALK: CONGRESS; Seeking Redress for an Old Wrong.” The New York Times. Published September 17, 1987. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/17/us/washington-talk-congress-seeking-redress-for-an-old-wrong.html.

“Norman Mineta.” Densho Encyclopedia. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Norman_Mineta/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

“Photo Gallery.” National Park Service. Updated April 28, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/photosmultimedia/photogallery.htm.

“Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II.” The Japanese American Citizens League. Published April 27, 2013. https://jacl.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Power-of-Words-Rev.-Term.-Handbook.pdf.

Ringle, Ken. “What Did You Do Before The War, Dad?” The Washington Post. Published December 6, 1981. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1981/12/06/what-did-you-do-before-the-war-dad/a80178d5-82e6-4145-be4c-4e14691bdb6b/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.9fceb80844ab.

Rogers, Everett M. , and Nancy R. Bartlit. Silent Voices of World War II: When sons of the Land of Enchantment met sons of the Land of the Rising Sun. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press. 2005.

“Santa Anita (detention facility).” Densho Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Santa_Anita_(detention_facility)/. Accessed September 28, 2018.

Seelye, Kathrine Q. “A Wall to Remember an Era’s First Exiles.” The New York Times. Published August 5, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/06/us/06internment.html.

Taylor, Alan. “World War II: Internment of Japanese Americans.” The Atlantic. Published August 21, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/08/world-war-ii-internment-of-japanese-americans/100132/.

“Transcript of Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942).” www.ourdocuments.gov. Updated September 28, 2018. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=74&page=transcript.

United States. 1983. Personal justice denied: report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Washington, D.C.: The Commission.

“War Relocation Authority.” Densho Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/War_Relocation_Authority/. Accessed September 26, 2018.

Weik, Taylor. “Behind Barbed Wire: Remembering America’s Largest Internment Camp.” NBC News. Published March 16, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/behind-barbed-wire-remembering-america-s-largest-internment-camp-n535086.

“WWII Internment Timeline.” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/timeline.html. Accessed September 28, 2018.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

“AFSC Oral History Project: Japanese American Internment.” American Friends Service Committee. https://www.afsc.org/document/afsc-oral-history-project-japanese-american-internment.

“Allegiance: A New Musical Inspired by a True Story.” http://allegiancemusical.com/.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community. https://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=HISTORYExclusionInternment.

“Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/miin/learn/historyculture/bainbridge-island-japanese-american-exclusion-memorial.htm.

Ichikawa, Akiko. “How the Photography of Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams Told the Story of Japanese American Internment.” HyperAllergic. Published September 1, 2015. https://hyperallergic.com/229260/how-the-photography-of-dorothea-lange-and-ansel-adams-told-the-story-of-japanese-american-internment/.

“Japanese Americans Interned During World War II.” Telling Their Stories–Oral History Archives Project. http://www.tellingstories.org/internment/index.html.

“Japanese Relocation and Internment–NARA Resources.” The National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/military/japanese-internment.html.

“Know Your Enemy–Japan (1945): Full Synopsis.” TMC. http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/496831/Know-Your-Enemy-Japan/full-synopsis.html

https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation.

“Oral History.” Densho Encyclopedia. https://densho.org/category/oral-history/.

“Selected Primary Sources on Japanese Internment.” Research Guides @ Tufts. https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/c.php?g=248894&p=1657724.

“The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from Japanese American Internment Camps.” thesmithsonianmag.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/category/history/the-art-of-gaman-arts-and-crafts-from-the-j/.

[i] Know Your Enemy—Japan, directed by Frank Capra (1945; Washington, DC: The U.S. National Archives, 2016), Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvcE9D3mn0Q.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Curtis Munson, “The Munson Report,” published in November 1941, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/japanese_internment/munson_report.cfm.

[vi] Ken Ringle, “What Did You Do Before The War, Dad?” The Washington Post, published December 6, 1981, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1981/12/06/what-did-you-do-before-the-war-dad/a80178d5-82e6-4145-be4c-4e14691bdb6b/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.9fceb80844ab.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] “A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II,” National Park Service, updated in April 1, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/articles/historyinternment.htm.

[ix] “Interning Japanese Americans,” National Park Services, updated November 17, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/worldwarii/internment.htm.

[x] “Transcript of Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942),” www.ourdocuments.gov, updated September 28, 2018, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=74&page=transcript.

[xi] “Japanese Relocation During World War II,” The National Archives, updated April 10, 2017, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation.

[xii] “WWII Internment Timeline,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/timeline.html, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xiii] “Santa Anita (detention facility),” Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Santa_Anita_(detention_facility)/, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xiv] “War Relocation Authority,” Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/War_Relocation_Authority/, accessed September 26, 2018.

[xv] Everett M. Rogers and Nancy R. Bartlit, Silent Voices of World War II: When sons of the Land of Enchantment met sons of the Land of the Rising Sun (Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2005), 155.

[xvi] Yoshinori H.T. Himel, “Americans’ Misuse of ‘Internment,’” Seattle Journal for Social Justice, vol. 14, no. 12: 2016, 801, 810-1, and 816.

[xvii] Ibid., 810 and 816.

[xviii] Ibid., 816

[xix] Taylor Weik, “Behind Barbed Wire: Remembering America’s Largest Internment Camp,” NBC News, published March 16, 2016, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/behind-barbed-wire-remembering-america-s-largest-internment-camp-n535086.

[xx] “Photo Gallery,” National Park Service, updated April 28, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/photosmultimedia/photogallery.htm.

[xxi] Alan Taylor, “World War II: Internment of Japanese Americans,” The Atlantic, published August 21, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/08/world-war-ii-internment-of-japanese-americans/100132/.

[xxii] Nathan, C. Nash, “WASHINGTON TALK: CONGRESS; Seeking Redress for an Old Wrong,” The New York Times, published September 17, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/17/us/washington-talk-congress-seeking-redress-for-an-old-wrong.html.

[xxiii] “Daniel K. Inouye, A Feature Biography,” United States Sentate, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Featured_Bio_Inouye.htm, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xxiv] “Norman Mineta,” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Norman_Mineta/, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xxv] “MATSUI, Robert T.” History, Art & Archives–United States House of Representatives, http://history.house.gov/People/Detail/17631, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xxvi] United States, 1982, Personal justice denied: report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Washington, D.C.: The Commission, 18.

[xxvii] Ibid., 3.

[xxviii] IRVIN MOLOTSKY and SPECIAL TO THE NEW YORK TIMES, “Senate Votes to Compensate Japanese-American Internees,” The New York Times, published April 21, 1988,

https://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/21/us/senate-votes-to-compensate-japanese-american-internees.html.

[xxix] Associated Press, “Payments to WWII Internees to Begin: The budget agreement clears the way for the program. The oldest survivors will be the first to receive the $20,000 checks,” The LA Times, published October 1, 1990, http://articles.latimes.com/1990-10-01/news/mn-1299_1_budget-agreement.

[xxx] “Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism during World War II,” National Park Service, updated February 16, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/places/japanese-american-memorial-to-patriotism-during-world-war-ii.htm.

[xxxi] “Interning Japanese Americans.”

[xxxii] Himel, 801.

[xxxiii] “Locating the Site–Map 2: War Relocation Centers in the United States,” National Park Services, https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/89manzanar/89locate2.htm, accessed September 28, 2018.

[xxxiv] Himel, 789.

[xxxv] Ibid., 810 and 816.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 801.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 798.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 833.

[xxxix] “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II,” The Japanese American Citizens League, published April 27, 2013, https://jacl.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Power-of-Words-Rev.-Term.-Handbook.pdf.