Women at Los Alamos

Only a small fraction of the women at Los Alamos worked as scientists. Most women found themselves at the Hill because their husbands had been recruited to work on the Manhattan Project. Isolated from the outside world by barbed-wire fences, and from the intellectual life of the Lab by the stringent regulations which prevented scientists from discussing the project with their spouses, these women had to create new lives and identities for themselves.

Secrecy and Seclusion

The memoirs written by many of Los Alamos’ female residents identify life in isolation and secrecy as a heavy burden for most women to bear. Ruth Marshak, the wife of physicist Robert Marshak, followed him to Los Alamos, later recalling the intense secrecy surrounding the community:

I was one of the women thus bound for an unknown and secret place. “I can tell you nothing about it,” my husband said. “We’re going away, that’s all.” This made me feel a little like the heroine of a melodrama. It is never easy to say goodbye to beloved and familiar patterns of living. It is particularly difficult when you do not know what substitute for them will be offered you. Where was I going and why was I going there? I plied my husband with questions which he steadfastly refused to answer…

My concerns as a housewife over the mechanics of living seemed rather petty in the face of the secrecy surrounding our destination. I felt akin to the pioneer women accompanying their husbands across uncharted plains westward, alert to danger, resigned to the fact that they journeyed, for weal or for woe, into the Unknown…

The fence penning Los Alamos was erected and guarded to keep out the treasonable, the malicious, and the curious. This fence had a real effect on the psychology of the people behind it. It was a tangible barrier, a symbol of our isolated lives. Within it lay the most secret part of the atomic bomb project. Los Alamos was a world unto itself, an island in the sky.

Women at Work

Apart from the shortage of woman power, which slowly decreased as single girls joined the project, it was an established policy to encourage wives to work. Colonel Stafford Warren, the head of the Health Division of the Manhattan District, placed little faith in women’s moral fortitude. In the early days of the project he declared himself in favor of giving work to the wives to “keep them out of mischief.” The wives were only too happy for an opportunity to peek inside secret places, to share the war effort, to earn a bit of money. I worked three hours, six mornings a week, as clerical assistant to the doctor’s secretary in the Tech Area. I was classified in the lowest category of employees, for I had no special experience or college degree… So, in Los Alamos I was paid at the lowest rate for my three daily hours, which was not much; but I was kept busy, happy, and “out of mischief.” I was given a blue badge that admitted me to the Tech Area but did not permit that I be told secrets; these were all saved for the white badges, the technical personnel.

Women who did not work faced challenges of their own, as they struggled to keep things normal despite the extraordinary circumstances that took their families to New Mexico. Their concerns were no different than those of other wives and mothers across the country: a decent standard of living, good schools for their children, an effective network of support, and accessible health care.

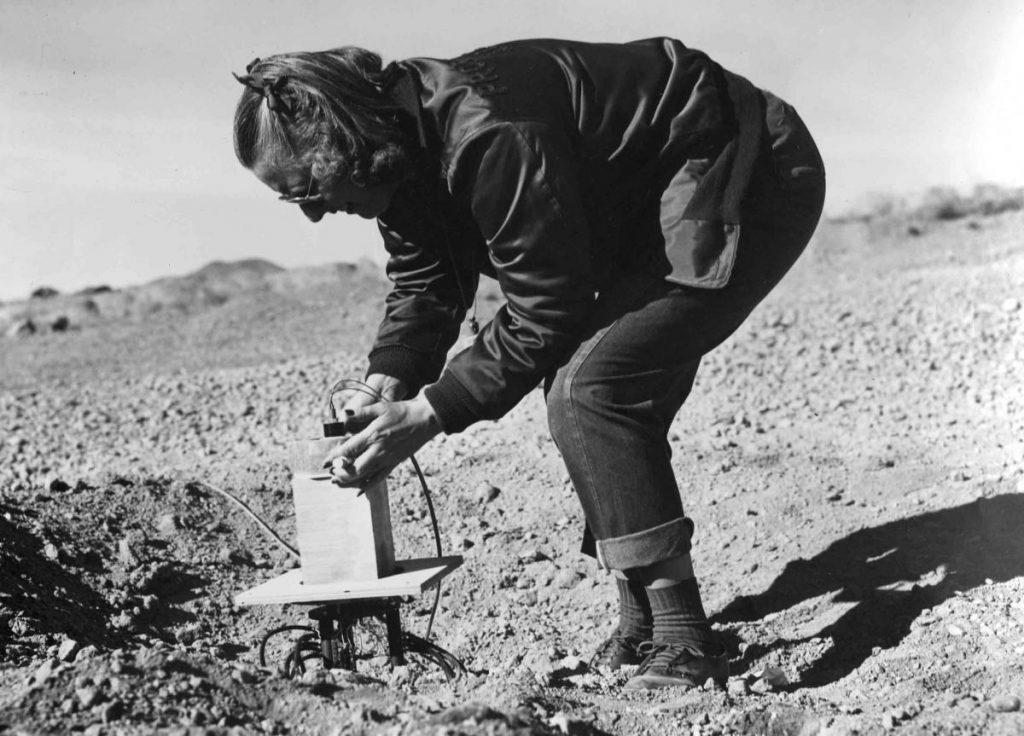

Women Scientists

In Cabin 4 the Graves’ spread out their equipment on the creaky double bed and told the inquiring owner that they were on a cross-country trip and would stay only two nights… In Carrizoso, Al Graves anxiously watched his wife puttering with the Geiger counter that rested on the window sill facing Trinity forty miles westward. Diz Graves was seven months pregnant, and Al worried that the strain of the last hours might injure her health. He put a steady arm around her and drew her to him. Over the short-wave set they could hear Sam Allison conversing excitedly with the pilot of the B-29. The Graves’s made a last check of their instruments. Then together they waited….

Women at Hanford

Like at Los Alamos, women living and working at Hanford also dealt with immense isolation. The turnover at Hanford for construction employees varied between 8 and 21 percent over the course of the project. Women were especially isolated. Single men and women lived in separate barracks and in dormitories surrounded by high barbed wire fences. The gate was guarded 24/7, requiring residents and visitors to sign in and out.

Hanford also had the smallest number of WACs of the three sites, with sixteen to twenty-four women posted to production work, compared to 260 at Los Alamos.

Family at Hanford

Although the population at Hanford was vastly dominated by single men, Hanford did have families living around the site. But unlike Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, they did not have the infrastructure most families during the 1940s relied on.

“I was a typical housewife. They didn’t have a nursery school, so I kept my daughter at home. There were very few children to play with because so few people had children.” –Meta Newson Interview for S.L. Sanger, 1986.

“There was no domestic help to clean your house. Most of us were used to having at least once a month, having somebody come in to do that kind of thing. A lot of people were used to nursemaids. It was tough, but of course we didn’t go out very much. There were some teenagers. They were looking for some-thing to do. We formed a babysitting group, with rules and regulations, and those kids earned money hand over fist.” –Betsy Stuart Interview for S.L. Sanger, 1986.

Women at Oak Ridge

Women at Oak Ridge also contributed to the settlement of the town. They worked and volunteered both with the Manhattan Project and establishing the greater community, largely responsible for creating and raising money for endeavors like the playhouse and music hall.

Women at Oak Ridge also contributed to the settlement of the town. They worked and volunteered both with the Manhattan Project and establishing the greater community, largely responsible for creating and raising money for endeavors like the playhouse and music hall.

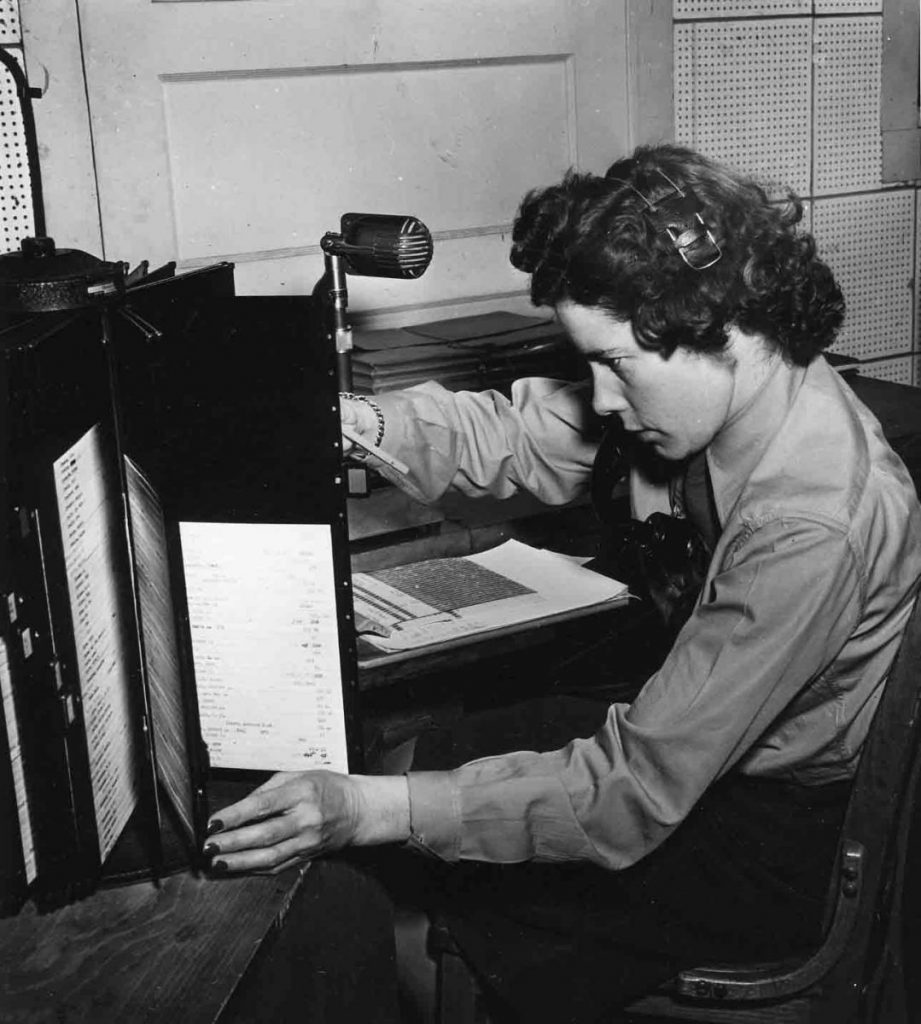

The Calutron Girls

The Y-12 Plant at Oak Ridge had 22,000 workers running the calutrons, large machines based off of Ernest Lawrence’s design at the University of California, Berkeley to separated Uranium 235 and 238. While at Berkeley the machines were operated by PhDs, the calutrons at Oak Ridge were most often operated by women recruited by the Tennessee Eastman Company, usually just out of high school. Yet, these women had the calutrons outperforming their more educated counterparts. Even without full knowledge of what they were doing, common for many employees at Oak Ridge because of the strict security protocols throughout the Manhattan Project, these women made an extraordinary contribution to the war effort.